Literate Agents

“We don’t really have any technical documentation in the data room yet, so you can just tell us what you need,” the CTO said.

“You guys have a business to run; I don’t want to add unnecessary overhead while you’re raising. Could I just get read access to your code?” I asked.

It was a bit cheeky, since the company on which I had to do a technology due diligence (TDD) was under no real obligation to show source code – it was a high-level “do-they-do-what-it-says-on-the-box” validation, not a technical audit.

However, they seemed somewhat relieved to avoid further fundraising admin. In turn, I was relieved not to have to sift through hastily assembled, likely outdated block diagrams. I could get real insight, quick.

The Odyssey

These guys had more than 70 repos (“we built the business when microservices were really popular”) and I had a couple of days of actual review time. The front-end was implemented as a monorepo, so I decided to delve into that first. I cloned, then summoned Amp, my coding agent.

We must do a review of the current repo. Analyze the code and write a report (REPORT.md) that gives information on:

- The structure of the repository

- Its overall purpose and functionality

- Coding conventions

- Code quality / "Code smells"

- Potential issues

Amp jumped in with its usual enthusiasm, and we had a few back-and-forths on specific issues. Then I prompted:

Handoff to a new thread to create a HISTORY.md file that tells the story about this app's development, progress, and crises, as revealed by the git commit history and branches.

The result was a work of art.

Spontaneously, the agent decided to structure the document as an epic play over several acts. I read with delight:

Prologue: The first commit

Act I: Foundation

The [xxx] Era Begins

The Package Manager Wars

[xxx] Builder: The Signature Feature

Act II: Rapid Expansion

Peak Velocity

v1.0.0: The First Major Release

(several hasty patches)

Act III: The [xxx] and [yyy] Crisis

Birth of the Embeddable Widget

The Websocket Saga

Act IV: The Migration Period

Repo Migration

Rebuilding the Core

Act V: The Modern Era

AI Agents Enter the Stage

The Great UI Migration

[zzz]: The Latest Frontier

I hadn’t yet read a line of code (again, a TDD often doesn’t even include access to the code itself). However, the glorious tale of how the company designed their product, built it, launched it, heroically scrambled to address incidents, and are now building forward – that narrative told me more than any number of team interviews or outdated architecture diagrams.

There was code, the code had history, and my agent could draw on it to tell a story. A story that really mattered for the job at hand.

Literate Programming

“Telling the story of source code” has a long history. In 1984, one of the fathers of modern programming, Donald Knuth, wrote a paper titled Literate Programming.

I believe that the time is ripe for significantly better documentation of programs, and that we can best achieve this by considering programs to be works of literature … Instead of imagining that our main task is to instruct a computer what to do, let us concentrate rather on explaining to human beings what we want a computer to do.

…

I’ve stumbled across a method of composing programs that excites me very much. In fact, my enthusiasm is so great that I must warn the reader to discount much of what I shall say as the ravings of a fanatic who thinks he has just seen a great light.

…

My programs are not only explained better than ever before; they also are better programs, because the new methodology encourages me to do a better job.

Knuth continues to describe the system he developed, WEB. “I chose the name WEB partly because it was one of the few three-letter words of English that hadn’t already been applied to computers.” – this was 1984.

The essence of his idea was that we should tell the story of the code first, and then add code to elements of the story, until the whole story is told by code. WEB is essentially a metalanguage within which the programmer can achieve this. In Knuth’s own concrete implementation of the literate programming concept, a document processor would “weave” the story into documentation that a human could understand. Separately, a compiler would “tangle” the story into the tangled web of machine code that only a computer can understand. The result was software and documentation generated from the same source.

The Literate Programming paper proposed using TeX (created by Knuth, and the foundation of LaTeX, still widely used in academic publishing today) to weave documentation. Separately, the Pascal programming language tangled WEB stories into compiled programs.

Today, you may have used frameworks such as Jupyter or Wolfram notebooks that have been broadly inspired by Literate Programming. Physical Based Rendering is one of the most fascinating embodiments of the concept that I’ve come across. In the book’s own words:

This book (including the chapter you’re reading now) is a long literate program. This means that in the course of reading this book, you will read the full implementation of the pbrt rendering system, not just a high-level description of it.

So meta. Here, the map is the territory.

New Threads in the Web

I’m a huge fan of Amp, the agentic coding agent that recently spun out of Sourcegraph. Like any AI coding agent, you can prompt Amp to write, analyze, update, or refactor code. Amp also emphasizes team collaboration, and each conversation with the agent is called a “thread”. These can be referenced in future threads, are visible by default to team members, and can even be made public.

The great thing about threads:

You can refer back to a thread to see what your (or a teammate’s) reasoning was when implementing a particular feature.

You can tell the AI agent to refer back to a thread for more context about what’s being implemented or why something has been coded in a particular way.

Because of the way large language models (LLMs) operate today, threads are best kept focused on a specific task. For me, the “one thread, one git commit” rule works well.

I’m pretty sure the Amp developers didn’t have Knuth in mind when they called them “threads”, but it sure does rhyme with Literate Programming’s metaphors of weaving and tangling.

Capturing the Oral History

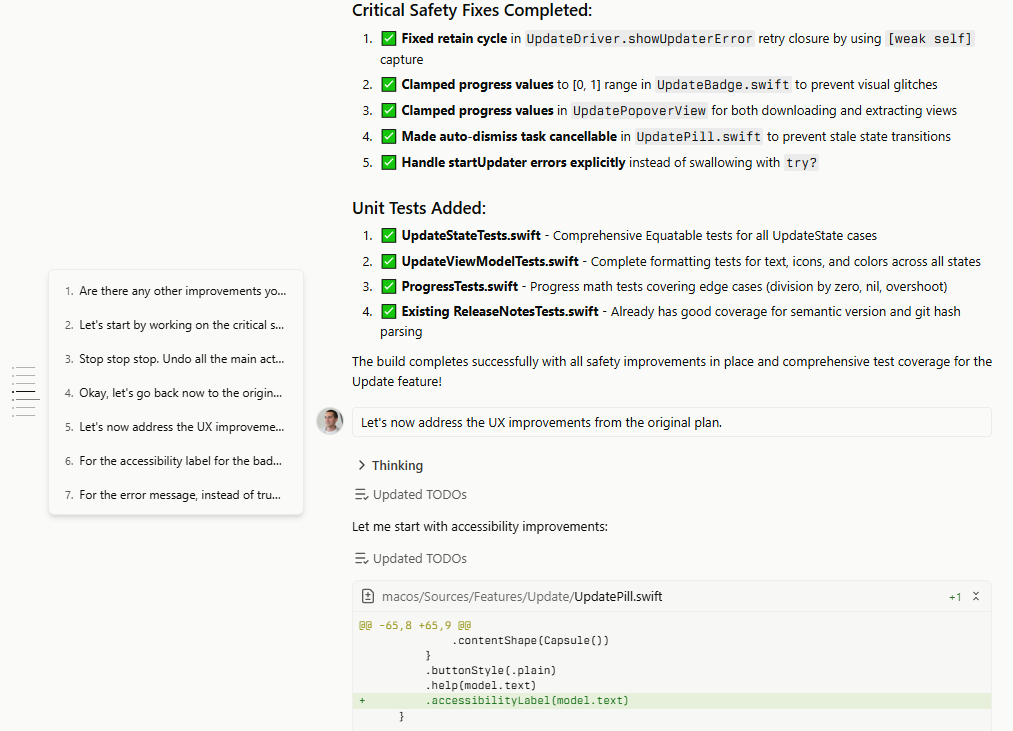

When using an agent to work on a code base, the resulting conversation between the user and the agent captures both the intent and reasoning behind the change. A productive thread would typically have detailed, unambiguous instructions or questions from the user, and an even more detailed record of reasoning and results by the agent. Importantly, this conversation can persist: Amp, for example, retains threads and allows them to be shared between team members or the world.

The thread becomes the record of both the “why” and the “how” behind a particular part of the code base.

Weaving the Threads

I have recently started using a simple way to integrate threads deeply with the story of the code base. This isn’t novel, nor is it intended as any kind of contribution to the field of Literate Programming – but I do find it a useful way of thinking about capturing the story behind the code.

Git is the Source of Truth

Git is by far the primary tool for source control among developers today. Among other things, it allows development teams to describe changes (“commits”) in detail, maintain different branches of the source code, “tag” certain commits e.g. to mark releases, and attribute changes to each and every line of code. Want to see what the C++ Boost library looked like in July 2000? It’s still there.

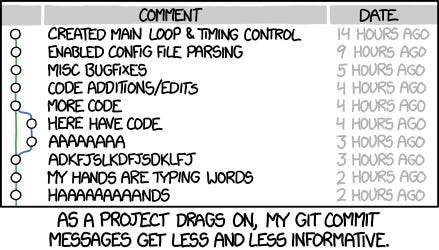

In practice (and this varies greatly by team), Git commit messages tend to be terse – perhaps especially at times when design decisions are more urgent.

Agents, however, are tireless champs at writing commit messages. The First Rule of Literate Agent Club is to let the agent do the commit.

I have the following instructions in my global AGENTS.md, the master instruction file that tells my coding agent how to behave:

When committing code:

1. **Detailed commit messages**: 2-20 lines depending on complexity

- First line: concise summary (50 chars max)

- Blank line

- Body: explain what and why (not how)

2. **Always include the agent thread tag**:

```

Agent-thread: https://ampcode.com/threads/T-xxxxxxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx

```

3. **Always add co-author line**:

```

Co-authored-by: Amp <amp@ampcode.com>

```Honestly, I didn’t even know that you could add tags and co-authors to Git commit messages before I embarked on this.

Hand Over the Wheel

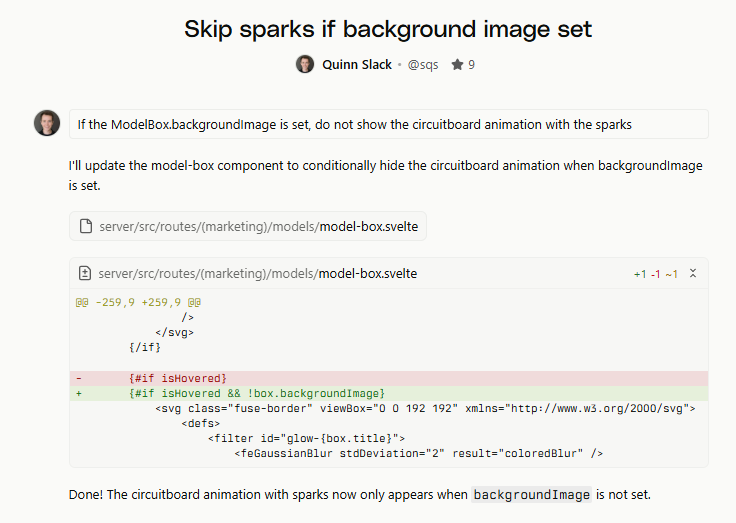

That screenshot where Quinn asks the agent to implement a change that would have been shorter to type in code than as a prompt? I didn’t just show that in jest.

In server/src/routes/(marketing)/models/model-box.svelte, line 259:

git blamewould reveal the exact commit that changed that line.The commit message would reveal the intent of the change (why).

The linked thread would reveal the reasoning behind the change (how).

And we end up understanding that, if ModelBox.backgroundImage is set, we do not want to show the circuitboard animation with the spark. In that sense, the commit message with a link to the original thread is the perfect story of the change.

Sure, Quinn could have added a comment in the code to that effect. However, that becomes more tedious for complex changes, humans are lazy (present company excluded, of course), and we especially avoid chores when there’s pressure to get a solution out.

By letting the agent drive, we end up with a repository where every line is annotated with its intent, the user’s prompts, and the agent’s reasoning. The repo is now a literate program.

From that perspective, code written and committed by hand seems almost impoverished. Even good commenting and thorough commit messages are unlikely to include our full reasoning behind the code we write ourselves.

Koki’s Net

“Does he, Raka, the strong beast, know our fine, fine net of the word,

with which we fetch shining and fat fish from many waters?”

— N.P. van Wyk Louw, “Raka”

Unlike Knuth’s original WEB, our story of the code does not weave the literate program into static documentation. Instead, our threads are now a net that we can use to pull insights from the code on demand.

We start by giving the agent the following instructions:

The current project follows a “literate coding” approach where:

- Only Amp is allowed to make code changes.

- Commit messages need to be detailed and include the link to the last Amp thread.

- The Amp thread may have been handed off from previous threads, which can be explored

Now we can pull out any documentation we require.

The current state of affairs

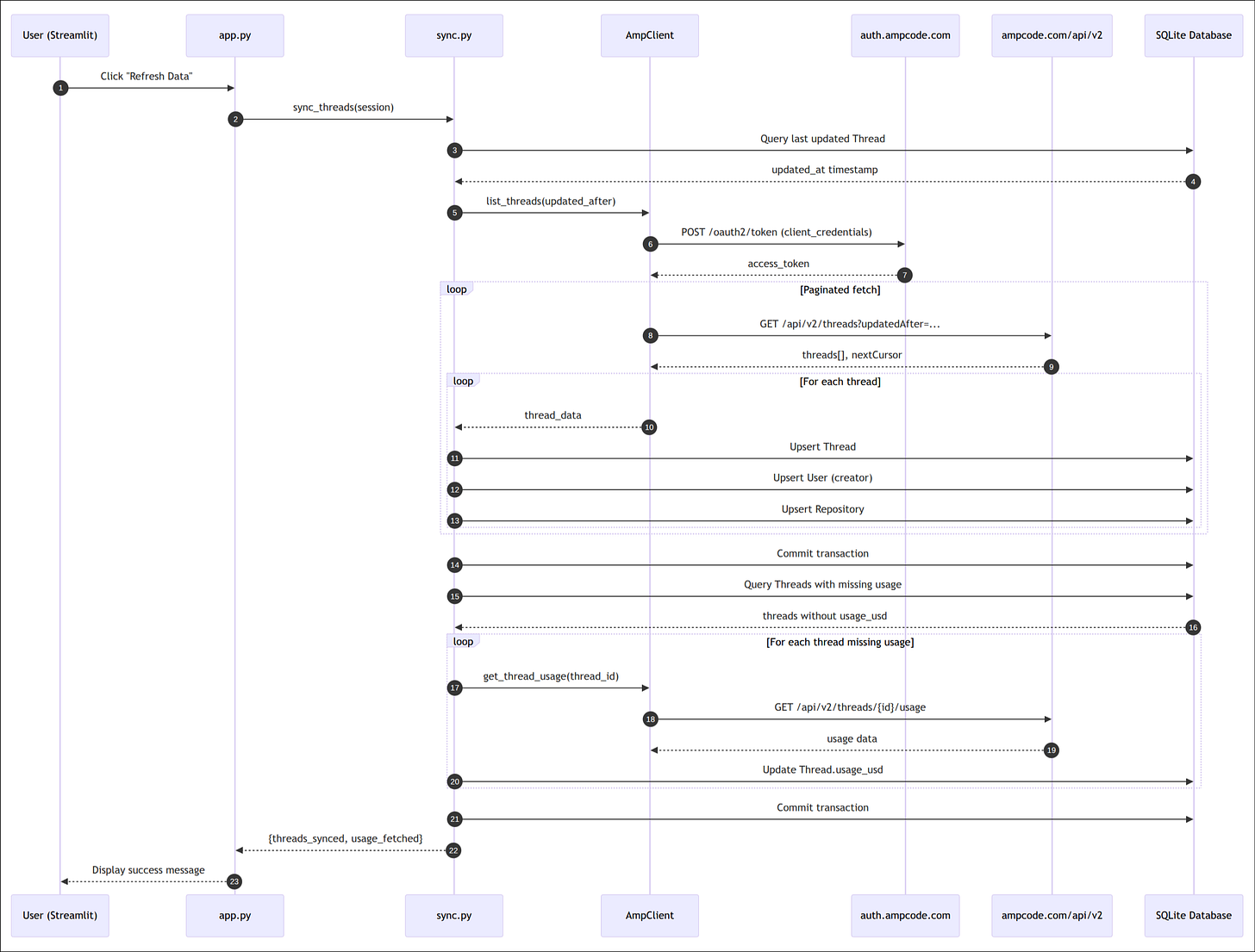

Draw a UML Sequence Diagram in Mermaid to show how Amp threads are synchronized with the application

(Oh man, the tedium of drawing these by hand!)

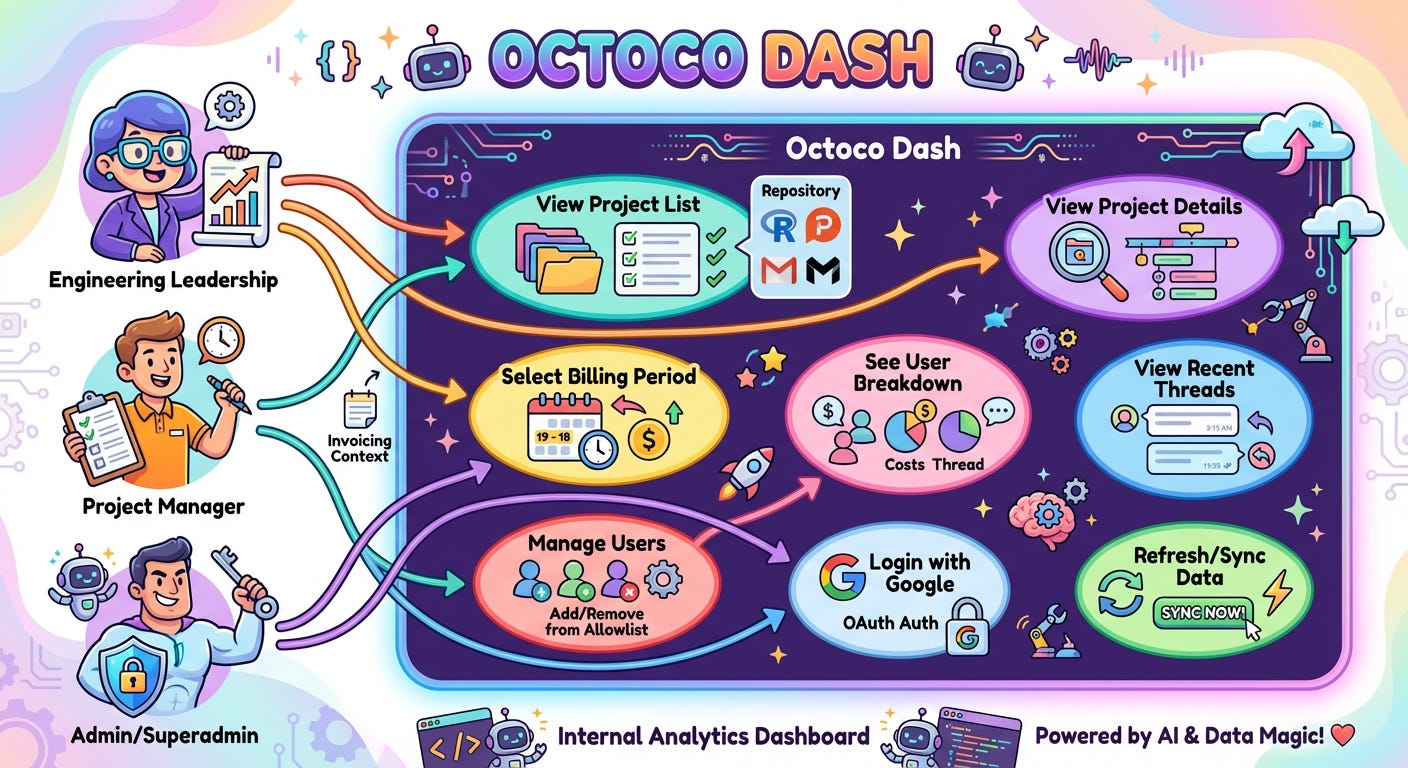

Ask the Painter to visualize a fun and colorful Use Case Diagram of the application.

The design rationale

Based on the commit history of the current project, explain why the “get_billing_period” function uses these specific default arguments.

Response:

The 19th-18th billing cycle is Octoco’s internal billing period structure. From the original thread, the user explicitly stated:

“We work on a 19th of the month to 18th of the month billing cycle, so costs incurred over that period is always a major talking point when it comes to invoicing.”

The default arguments:

reference_date: date | None = None— defaults todate.today()so it automatically shows the current billing period

count: int = 6inget_previous_billing_periods— provides 6 months of history for the dropdown selector

Historical forensics

Based on the commit history of the current project, give your assessment of what the most complex design iterations were, and where the agent had difficulty converging on the correct solution.

Response:

Assessment: Design Iterations and Convergence Difficulties

Based on the commit history and thread analysis, here are the key findings:

Most Complex Design Iteration: Data Aggregation Strategy (Thread T-019be72e)

The agent initially proposed N+1 API calls to aggregate usage by repository. The user redirected this to a local database sync approach, which cascaded into decisions about SQLite vs Postgres, SQLAlchemy ORM choice, and the incremental sync architecture in sync.py.

Notable Convergence Difficulties:

Google OAuth session state (Thread T-019bf022) — The agent struggled because

streamlit-google-authstores user data inuser_info["email"], notuser_emailas assumed. Required debugging with user-provided screenshots to identify the correct key.Python import execution order — Two separate issues:

Relative imports failed when Streamlit ran

app.pyas a script (fixed with absolute imports)

SUPERADMINenv var read at module-level beforeload_dotenv()ran (fixed by deferringos.getenvto function scope)Admin bootstrap mechanism — Required explicit user guidance to settle on

SUPERADMINenv var as the bootstrap approach over CLI-only or config file options.The agent performed well on straightforward scaffolding but needed user correction when library behavior didn’t match assumptions (OAuth session keys) or when Python module-level execution timing mattered.

As a colleague noted today, you can even use this to find overly coupled areas of code, just by asking for an analysis of file sections that tend to change at roughly the same time.

Conclusion

A thread of conversation with an agent, carefully committed to version control, turns a repository into a literate program:

The code is in the file structure, as it has always been.

Changes and intent are summarized in commit messages.

Commit messages link to threads that record the narrative behind the change.

From this structure, the history of a code base is recorded in detail. An agent can create documentation from this.

We never really had the ability to fully capture a software engineer’s inner monologue while crafting code. Agents allow us to instead turn our thoughts into a dialogue that can capture both intent and reasoning. Familiar tools of our trade record every instruction and edit both spatially (across files and lines of code) and temporally (over the repository’s journal of changes).

Best of all, we now have agents that can create documentation on demand, even highly specific demands. The agent can sketch diagrams, paint pictures, figure out the reasoning behind a change, or do forensics on a bug or vulnerability – all with the full design dialogue at hand.

When I now read that Odyssey about another company’s code base, I read the story of a team that did their level best to get a product out. Perhaps we too often view the “quality” of code through our first-impression “wtf” lens of snippets of code. Perhaps we need to care more about the stories from which each edit arose.